Bringing back the Ink Print

Filed under: Ink Process, Cyanotype, Photography

Have you ever heard of the Ink Process? No? Well, neither had I till a few months ago.

If you have, then, well, you must read a lot of old german photography books. Cause that’s what I was doing when I came across the following recipe in the fifth edition of “Photochemie und Beschreibung der photographischen Chemikalien”1 from 1905.

- 10g of ferric sulfate

- 20ml of ferric chloride

- 10g of gelatin

- 10g of tartaric acid

- 300g of distilled water

In addition to that there is a developer made from 1L of water, 4g of gallic acid and 0.5-1g of oxalic acid.

This was described as the “Colas Tintenprozess” or “Colas Ink Process”, a black and white positive process patented in 18802 that at first glance looks incredibly similar to cyanotype, with a sensitizer made up of a source of iron in its +3 oxidation state and a dicarboxylic acid.

The interesting part though is the developer, which instead of consisting of potassium ferricyanide consists of gallic acid (and oxalic acid, but we’ll get to that later).

Now, if you know your old school inks you might recognize those ingredients as not only incredibly similar to those in cyanotype but also those in iron gall ink!

How does it work?

Before I go into explaining how the ink process works let’s take a quick look at how iron gall ink works.

According to whoever wrote the wikipedia article on it iron gall ink was the the most common ink used throughout europe between the 5th and 19th century. It consists of a source of iron(II) ions, usually from ferrous sulfate, and gallic or tannic acid, both dissolved in water. The gallic acid usually came from oak galls, weird growths on oak leaves created by a parasitoid wasp. Nature is freaky!

When mixed they would form a light brown and water soluble ferrogallate complex which could be used for writing. After some time the oxygen in the air would oxidize the iron(II) to iron(III), turning the water soluble ferrogallate complex into a dark purple-black and insoluble ferrigallate complex, rendering the writing permanent.

The Colas Ink Process™ uses that same difference in solubility between the ferrigallate and ferrogallate complex to form images! We start out with an iron(III) source, in this case ferric chloride and ferric sulfate, and mix them with tartaric acid which acts as reducing agent. Ferric chloride, especially when mixed with a mild reducing agent, is light sensitive, so as the image is exposed the iron(III) is reduced to iron(II) and the tartaric acid is decarboxylated.

When immersing the exposed image in the developer the gallic acid reacts with the iron, forming light and soluble ferrogallate everywhere the image was exposed and dark and insoluble ferrigallate wherever the image wasn’t exposed.

To me this is incredibly cool! First of all, it’s a positive black and white photographic process which alone is already kinda rare, but it’s also incredibly simple! No exotic chemicals. No cyanide. Just iron and some acids.

Let’s make some!

Luckily almost all of the required chemicals are very easy to get or to make yourself.

Tartaric, gallic and oxalic acid can easily be bought online. Ferric chloride can be bought in the form of PCB etchant as a 25% solution in water. If you want to go the extreme DIY route ferric chloride is easy to make yourself using hydrochloric acid, hydrogen peroxide and steel wool and the carboxylic acids could be extracted from various plants or substituted with less refined versions like black tea or coffee.

The only one that was slightly more tricky was the ferric sulfate. While ferrous sulfate is easily available ferric sulfate just doesn’t seem to have a ton of uses so it’s not sold a lot. I was able to just get it from a chemical supplier in the end, but if you have access to sulfuric acid you could also just make it yourself.

The original recipe also includes gelatin, but because I’m not into the whole dead animal thing I just left that out. It will thicken up the sensitizer and make it easier to coat, but I found just brushing it onto water color paper works fine even without the gelatin. It could probably be substituted for a number of other sizing agents or thickeners as well.

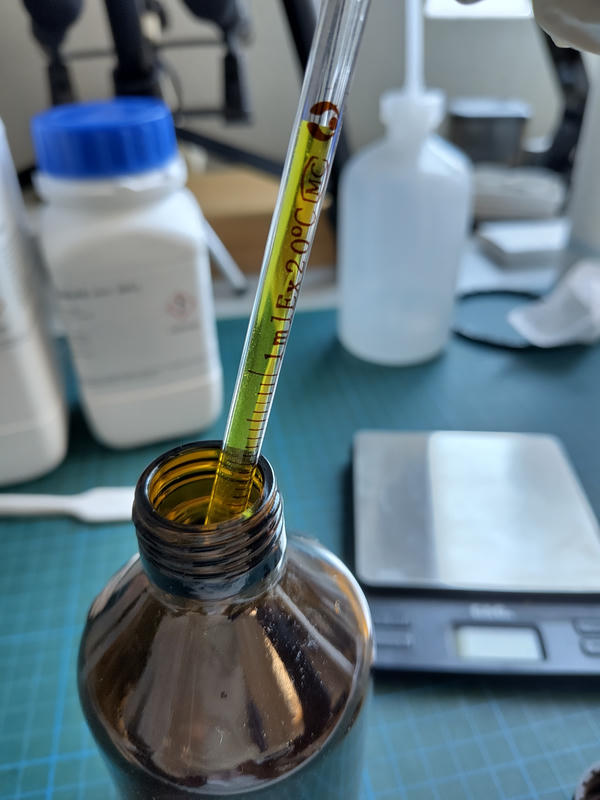

I prepared 250ml of the sensitizer and it seems to store well in a brown glass bottle when kept out of light. Keep in mind that this sensitizer is fairly acidic3, so it does somewhat attack the paper and gloves should be worn when handling it.

I similarly prepared 1L of the developer, which will slowly turn darker with use and as the ferrogallate dissolved in it slowly oxidizes, so it’s best to make a fresh batch just before use4. I found 1L of developer to be enough to develop around 4-5 A4 sized prints.

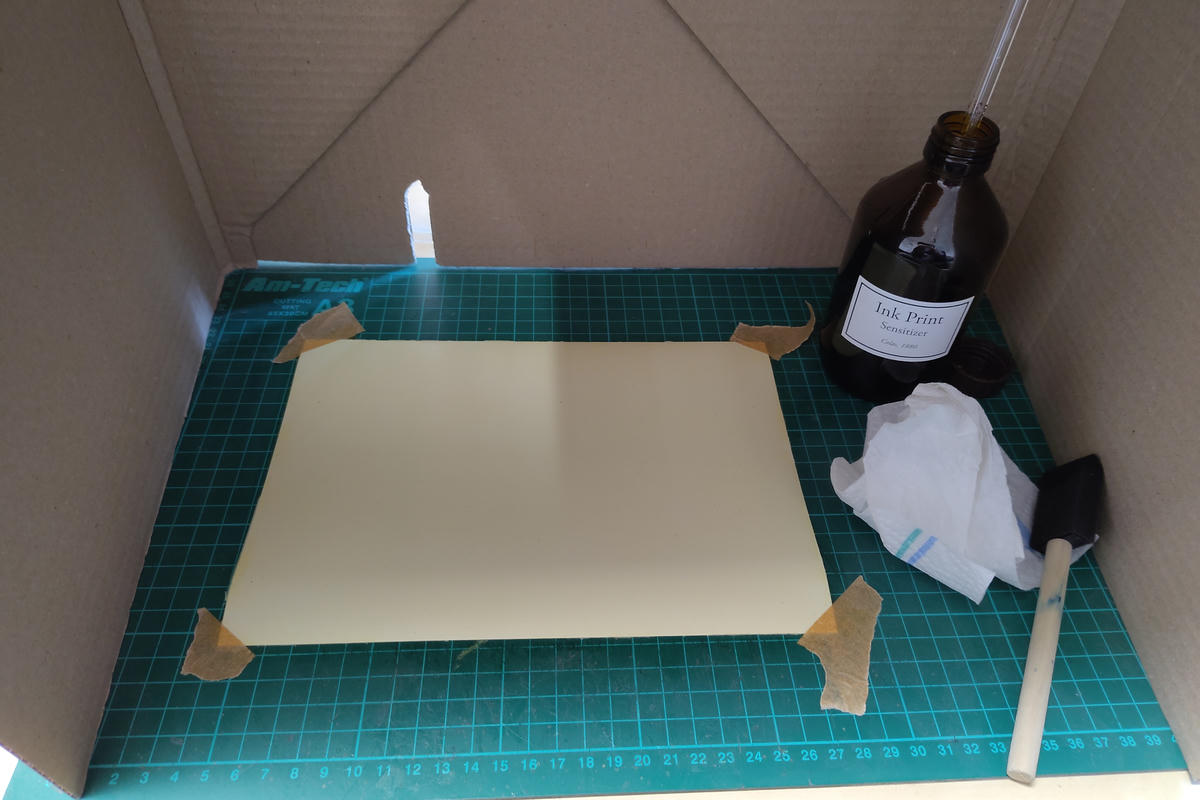

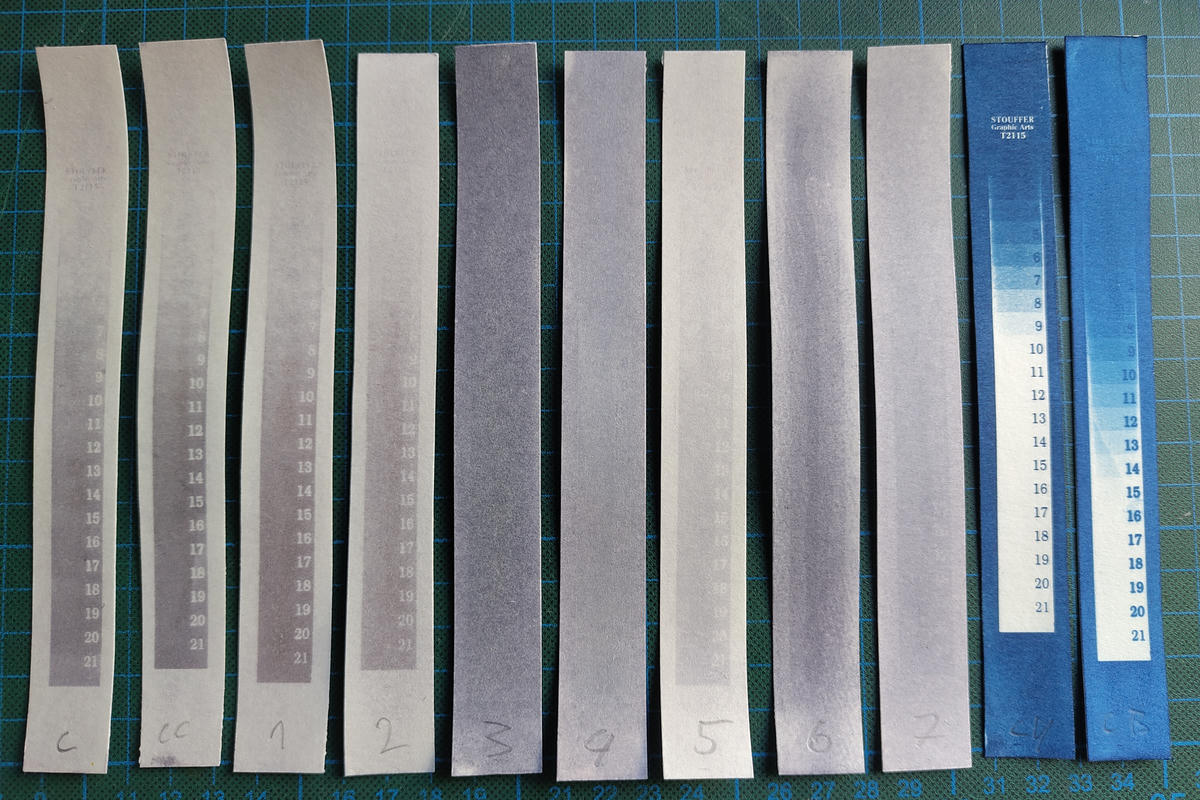

To sensitize the paper I applied a single coat of the sensitizer using a foam brush and let it dry in a dark place. When doing this it’s important to make sure the coating is very even since the density of the final print depends heavily on the amount of sensitizer in each location, much more so than with a negative process like cyanotype5.

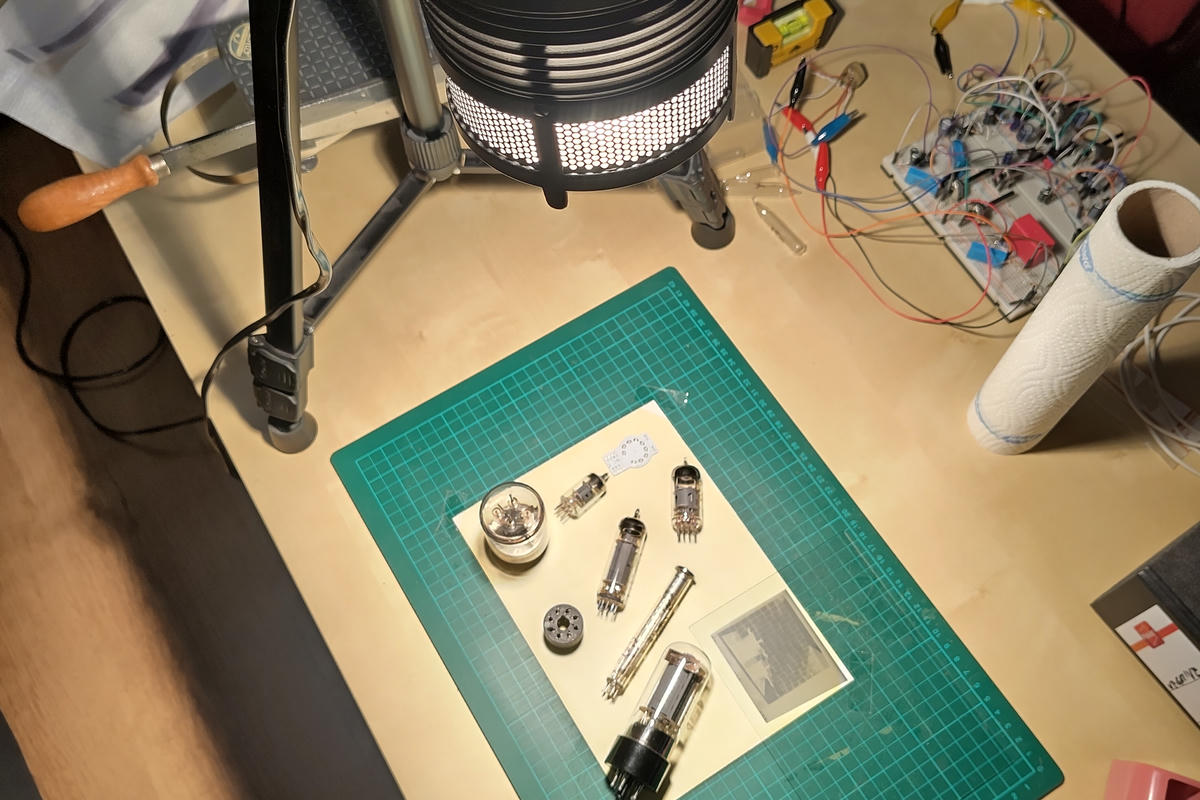

For my experiments I decided to make simple photograms since I felt the idea of capturing an object’s shadow as a positive fit very well with the æsthetic of the process. The images were exposed for 15 minutes using a 1000W halogen spotlight. A UV light or exposure box works as well and can results in exposure times as low as 5 minutes, but I preferred the sharper shadows and higher contrast I got from the spotlight.

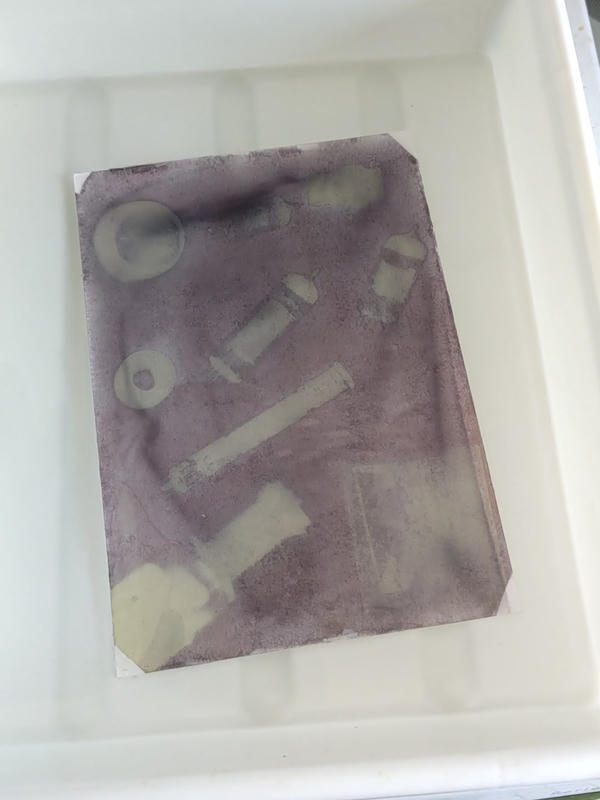

After the exposure was finished the prints were developed in a tray of the developer solution with constant agitation. This process takes quite a while and will first form a negative image which slowly washes away as the soluble ferrogallate dissolves and the insoluble positive ferrigallate image is revealed. You know it’s done when there is no more yellow visible and all the shadow areas are fully developed.

Afterwards the images were thoroughly rinsed and hung to dry.

Variations

So, this process is really cool, but can we make it better?

No, not really.

I tried various other carboxylic acids, like citric acid, maleic acid and oxalic acid but they all either produced no image at all or, in the case of the citric acid, only a very faint image.

The oxalic acid is rather interesting though. Oxalic acid is a relatively good reducing agent, good enough to reduce the insoluble ferrigallate back into soluble ferrogallate6. That’s bad for making an image, but actually explains why it’s included in the developer. The very small amount of oxalic acid in the developer acts as a bleaching agent, ensuring that the bright parts of the image fully clear up and prevents the paper from getting stained.

I also experimented with different sources of iron(III). It turns out that if you can’t find any ferric sulfate you can just use more ferric chloride instead. The image will be slightly less dense, but it works the same otherwise.

Using only ferric sulfate on the other hand doesn’t show any light sensitivity at all and results in a completely black image. I’m not sure what chemical role the ferric sulfate plays exactly, but in conjunction with the ferric chloride it does lead to a slightly denser image.

I also tried using the “traditional” cyanotype sensitizers like ferric ammonium citrate and ammonium ferric oxalate, but both of them resulted in a completely soluble image which just washed away during development.

The sensitizer as described by Colas is relatively dilute7, but as opposed to a negative process where increasing the concentration of the sensitizer makes it more sensitive the opposite happens here. Since the iron(III) in the sensitzer needs to be fully reduced to get the highlights of the image to clear increasing the concentration leads to a lower sensitivity while proportionally increasing the contrast and density.

So, the formula as developed by Colas in 1880 seems pretty optimal for making ink prints. The sensitivity is about the same as that of the classic cyanotype or maybe even a bit better, so don’t expect to use this inside a camera or even with an enlarger, but if you want true black and white contact prints and photograms it works great.

But what if we want to make cyanotypes instead?

Cross Processing Ink Prints?!

Ok, so, What if we… cross processed the ink print sensitizer as cyanotype using potassium ferricyanide?!

Yeah, that totally works! And since potassium ferricyanide doesn’t have any adverse reactions with the much more “sensitive” oxalic acid we can even use that instead of tartaric acid!

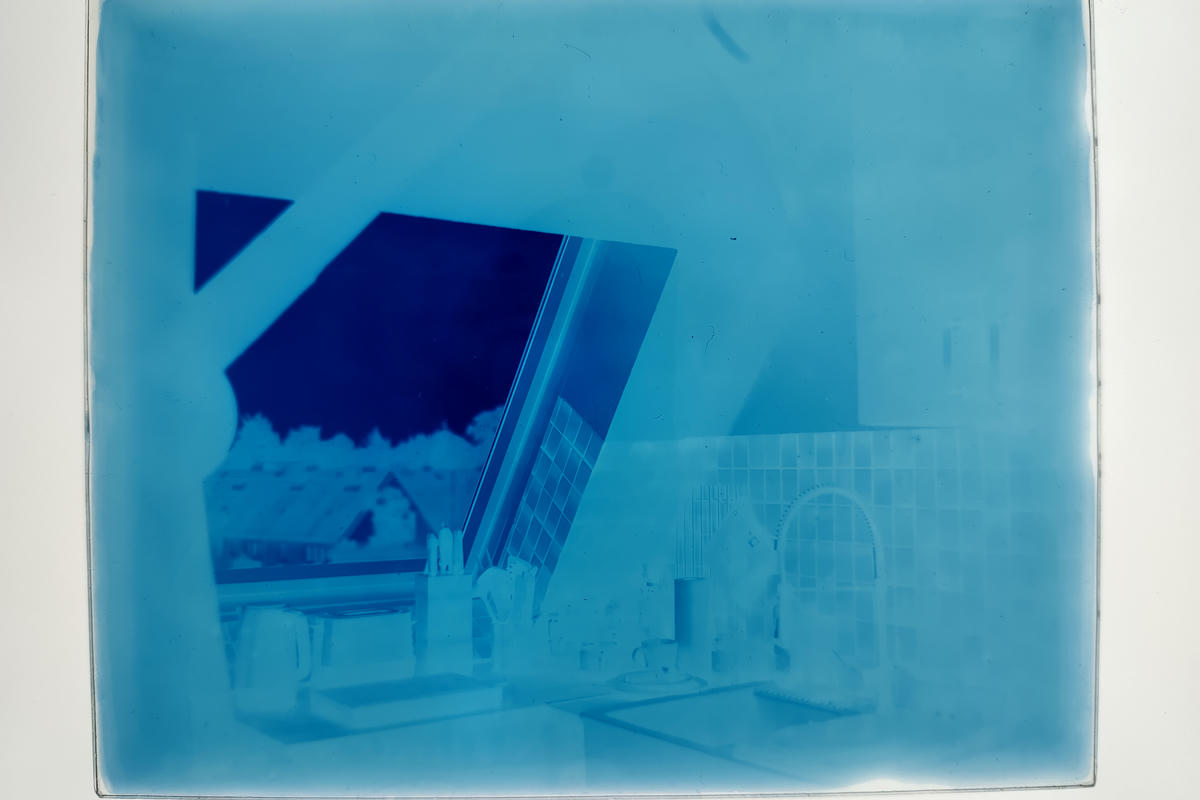

The low pH of the sensitizer causes a relatively large amount of fogging, but by replacing the pure oxalic acid with easy to make disodium oxalate I was able to produce one of my most sensitive cyanotype sensitizers yet! The above picture was taken in around half a day. There is still some base fog, but it seems to work very well for in-camera use if you want to scan the negatives or make prints from them later!

After a whole bunch of experimentation the final recipe for 100ml of this sensitizer is as follows:

- 10g of ferric sulfate

- 20ml of 25% ferric chloride solution

- 10g of disodium oxalate

- Distilled water to make 100ml

What I like about this sensitizer is that it is much easier to DIY than any of the other ones from basic off the shelf chemicals. Making ferric ammonium citrate is a pain, but this… just works! And I think it’s also a great demonstration of just how versatile cyanotype is. As long as there is some iron(III) and a suitable reducing agent you can probably use it to make a cyanotype!

Conclusions

Ink prints are cool! Go make some! And read some old books too!

Kris ^-^~

Fotnotes

Page 213-214, document available on archive.org here: https://archive.org/details/photochemieundbe00voge/

I tried my best to find the actual patent but couldn’t come up with anything. If you know how to get your hands on it please let me know!

It would be interesting to see if the sensitizer would also work with the tartaric acid substituted with cream of tartar, also knows as potassium bitartrate, since that would help reduce it’s acidity somewhat.

I also tried preparing a stock solution which could be diluted for use but gallic acid is not very soluble in water so it’s hard to actually get it to fully dissolve at higher concentrations.

There is actually something really interesting going on here I think! With a negative process like cyanotype the amount of pigment that is formed is proportional to the amount of light hitting each spot. As long as there are enough precursor chemicals present the final density isn’t very dependent on their actual concentration. But with the ink process dye precursors are destroyed by the action of light, so the final density in unexposed areas is just however much sensitizer was applied to that area.

Oxalic acid solutions were actually used to make corrections to documents written with iron gall ink since they could return it to its soluble state!

Though it’s also important to remember that the inclusion of gelatin would have probably lead to a significantly thicker layer of sensitizer when coating the paper.